I had my first ever on-the-job teaching observation after I’d been in my first job for a while: long enough to garner a bit of confidence; to love my class; to feel that they at least liked me a lot; and long enough to be out of my probationary period. On-the-job observations of non-probationary teachers are meant to be ‘developmental’. In practice, teachers often seem terrified of observations, unable or not helped to see any underlying developmental purpose, and generally harbouring a quiet suspicion that their job may be on the line.

And so it was with me in my first teaching observation. I spent hours preparing every day, but I prepared this even harder. It was a grammar lesson on the past continuous vs. past simple, and it was my best CELTA rendition – I presented, I controlled practised, I freer practised and I was terribly winning throughout. I came out feeling buzzed.

I sat down with my DOS, and he started with that horrible (but useful) CELTA stalwart question: ‘How do you think it went?’

Actually – I thought it went pretty well. I thought I’d explained the concepts well. I thought I’d shown the form clearly on the board. I thought the students had had a few problems that were highlighted during my photocopied controlled practice task from English Grammar in Use (Intermediate), but I thought I’d explained these clearly in feedback. It was a shame there hadn’t been much time for the freer practice in the observed lesson, but (I assured him) they were all using it really well in the next lesson. [I will always remember a much later observer, teacher trainer and friend telling me, tiredly: ‘It’s always better in the next lesson…’]

You may be able to spot some issues with the above. Maybe not – there were certainly good things there: awareness of (some) aspects of target language aims – identification of (some) appropriate material – good rapport. Anyway I tailed off after a while and asked my DOS: “How do you think it went?”

He said, and I quote, ‘To be honest, I thought it was pretty shit.’ [He was a northerner, if that explains anything]

His main points were:

– ‘Your aim was to get your students using the target language, yet most of the talking time in the lesson was you explaining things.’

– ‘There wasn’t very much talking time anyway, as you kept giving them paper exercises.’

– ‘It’s not about you or what you did. It’s about the students got from the lesson.’

Me (feebly): ‘But didn’t you think the exercises were useful? They highlighted [this or that] error and they really needed help with that.’

Him: ‘Yes but – you do know that Raymond Murphy is a self-study book for students right? If students can do something at home and check the answers themselves – why are you making them do it in class? Spend your class time doing useful things, things they can’t do by themselves at home!’ [Flipped Learning – still a thing in 1996, people]

He added: ‘You didn’t do anything on pron for instance.’

He was right. It wasn’t even on my radar. And it was a really good point about Murphy – I hadn’t realised that just because I had relied the crap out of this book to learn the grammar of my own language while doing CELTA, doesn’t mean that students needed that from me. They’d had years of controlled written practice of grammar points already. What they wanted, needed and were paying for was a chance to really use, relate to, internalise and engage with the language.

My DOS topped this off by saying, ‘Right. Here’s what we’re going to do. Next lesson, you observe me. I’ll show you some of the things I want to see you doing in class, and you can take notes on what/when/why and then we’ll talk about it afterwards.’

What I then saw wasn’t my first time watching someone elicit, model, drill and write up target language on the board – but it was the first time that I had been ready to see why and how it was useful, why it worked. Plus I got to see someone with my class; I got to see how quickly they could establish rapport through confident teaching rather than handouts-and-niceness-over-time; I got to see them modelling and drilling in a really fun and dynamic way; I got to see how students enjoyed and appreciated that; I got to see how easily a personalised task can be plucked from the air; and I got to see how easily students launched into it and loved it.

(Why aren’t more new teachers observing experienced teachers instead of [or as well as] being observed themselves? A question for another time…)

We met again after class, and talked this over, and it was good because my DOS conveyed that he was sorry for being so ‘northern’ the day before, and it was also clear that my job wasn’t on the line – he thought I did have the right stuff – but he wasn’t going to let me get away with just ‘having my awareness raised’. Being aware is not the same as putting into practice.

‘Right,’ he said. ‘Here’s what we’re going to do. I’m going to come and observe you every day for a week. And each day you have to teach the whole lesson based on just one page from the coursebook. No, not a double page. Strictly no supplementary materials. No, not even the workbook.’ [Dogme – still a thing in 1996…]

This was terrifyingly incomprehensible for a super planner who had to have 9 zillion handouts just to feel secure in any lesson. ‘But,’ I stammered, ‘the next page only has a couple of speech bubbles on it!’

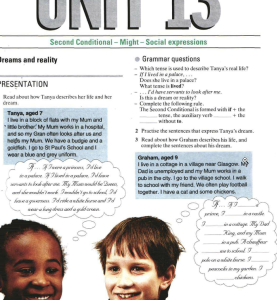

We were talking about this page, or something very like it:

At the time I literally could not imagine how it could be done.

But it could.

My warmer was a dictation. Normal style (read, listen, write, read, listen, write etc) for the first text, followed by pair check and group feedback on the board [Nowadays I’d do that as ‘the teacher is a recorder’ where students can shout ‘Stop! Rewind! Play! Fast forward!’ – one of the best no-mats activities ever).

The second was dictogloss style, again with pair check and feedback to the board. We then used the board text to examine the target language, ask concept questions, and elicit the form to the whiteboard. When we’d discussed the meaning and form of the target language I then copied my DOS and managed to focus attention, model clearly, beat the stress, and conduct choral and individual drilling in a really simple and clear way.

(I was amazed that my DOS’s arcane pron magic worked for me as well as it had for him. It was the first time I really ‘noticed’ pron for myself rather than as something just to churn out in a CELTA observation. It meant something, the students enjoyed it, wanted it, needed it – and couldn’t really get it from elsewhere.)

We then did a simple personalisation activity – I asked students to write a short description of their own life, e.g. I live…I work…I have…I go…They then swapped their paper with a partner who read their original sentence completion, then crossed it out and substituted it for something imaginary, writing a two-clause second conditional sentence (If I worked at X, I would Y etc.). Then they got together, read out their sentences and basically talked about their own realities and dreams.

For the first time in my teaching life I had the impression that a lesson flew by. Also for the first time I saw myself as a facilitator rather than the ‘sage on the stage’. And it was a big realisation that I had enough to offer as a teacher that I could carry a whole lesson without ever even opening the book; that materials aren’t an imperative but something to be exploited, turned around, made the most of, or ignored, depending on what would be of most benefit to the students.

The thing about having a ‘shit’ observation is that it can be the best thing that has ever happened to your teaching – and being observed every day for a week by someone who’s genuinely interested in your development is an amazing opportunity.

Have you had any eye-opening moments result from an observation?